I recently read a book that got me thinking about pop star Britney Spears. Or more specifically, her children. It wasn’t her bestselling memoir full of gossip snippets that I read. It was a guidebook for teens.

But let me back up. I’m familiar with Britney Spears’ music and great performance talent. I’ve also followed her personal life punctuated by mental illness, and her controversial thirteen year conservatorship riddled with major conflicts of interest (like her family members paying themselves high salaries off her earnings). And I’ve sadly watched the numerous videos the last few years, since the conservatorship ended, she posts to social media where she’s sometimes wearing odd attire, looks disheveled, inexplicably speaks with a pseudo-British accent, and frequently dances around her house and in public, more than once holding large knives. Videos in which her mental health, to my eyes, is clearly and sadly decompensating.

But I must admit that I’d never given much thought to Britney Spears’ two children in all of this, two young adults who recently chose to move to Hawaii to live with their father and reportedly have limited contact with her now.

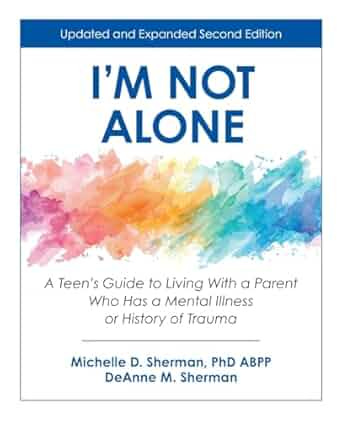

That is, until I read this book:

I’m Not Alone: A Teen’s Guide to Living With a Parent Who Has a Mental Illness or History of Trauma.

Last month a board certified, licensed clinical psychologist named Michelle Sherman reached out to me about my “Gaps” column, and how, through her work, she’d spotted a major gap in supporting children who live with a parent or guardian who suffers from a mental illness, and started writing about it. Which got me thinking more deeply about the topic, about so many celebrity cases we see in the news like Britney Spears, and about what I realized I’ve seen firsthand in families close to me.

Michelle was right. It’s a major gap that isn’t often discussed.

Beginnings

Michelle Sherman has always been interested in helping others, with a long history of volunteer work, including serving as a support for individuals in an ER after sexual trauma, and creating the first sexual assault support group on the University of Notre Dame campus.

In narrowing her focus on families and mental illness, she drew from both personal experience (mental illness in her family) and clinical work. While she was working at the VA Hospital in Oklahoma City in the late 1990s, she saw many family members sitting in the mental health clinic waiting rooms, and the “commonality of their needs and challenges and loneliness really spoke to my heart.” She started creating education programs for family members that offered support and information about helping someone who has experienced trauma or has a mental illness, as well as tools for taking care of themselves.

Then in the early 2000s, she asked her mother, a longtime experienced educator who knows how to engage people in a meaningful way, to co-write a book on the topic of teen support, and her mother agreed. They went on to write three together—one for those with a parent who has experienced trauma, one for teens whose parent has a mental illness, and one for those whose parent has a military deployment.

Children Are Often Invisible

In our chat, Michelle pointed out that often the “family system is focused on the person with the illness...that the children are often invisible.” Healthcare providers don’t consistently ask MH patients Do you have kids? much less How are your kids doing with your recent hospitalization or episode?

She went on to say that although providers may feel unsure what to say, or what resources to provide (as there are so few), she believe it’s essential that we “move the needle on all providers routinely asking and supporting these youth.” Several countries (like Canada, UK, Australia, and Iceland) have built in wonderful supports for their youth, and, she says, it’s really a “prevention move as we know these youth are at higher risk themselves for developing mental health problems.”

She was delighted to note that in Iceland, they’re using I’m Not Alone as part of family days and teen workshops held at their psychiatric units.

She developed the book through a review of the existing research on what the MH community already knows these children want and need. She noted that kids who’ve grown up with a parent with a SMI but were never told about the parent’s SMI have been studied, and research showed these children interestingly sometimes made up far scarier stories about what was going on at home than the reality. Therapists were then able to deduce they need to explain things to kids in developmentally appropriate ways.

Michelle and her mother also drew upon the research of resilience among youth, and developed the exercises and activities in the book together. Then, they pilot tested them on a large number of youth and youth-serving professionals to improve their work.

Teens Speaking for Themselves

The book is both informational and experience, with explanations of different MIs, causes, and treatments, with space for teen readers to record their own story, thoughts, and feelings. The final sections outline finding and getting support, how to talk to friends, and taking care of their own mental health.

One aspect of the book I found especially interesting was the inclusion of direct quotes from teens, speaking about lived experiences in their own words:

“Sometimes I tend to carry all his (my dad’s) emotions on my shoulders, in addition to all that I’m going through…deep down we love our parents, but I think it can become heavy.”

“It made me angry not to understand what was going on…anger towards myself, towards my mother, toward my family who didn’t explain things to me.”

“When she [my mom] was hospitalized, I always felt a sense of relief knowing she was safe and was being taken care of.”

Through her work with these families, Michelle most sees teens struggle with confusion and embarrassment about their parent’s illness, fear (Will I develop it?), shame (due to stigma), loneliness (e.g. how does their community respond when their parent is admitted to the hospital, and how is that different than if a parent has cancer?), powerlessness about how to help, sadness, anxiety and worry, and feeling unsure how to talk to their friends about it.

Finally, what Michelle would like the general public to know or understand most about this topic, is that half of us will experience mental illness at some time in a lifetime, and that most people know at least one to two people experiencing mental health problems. She believes family members of people managing mental health problems and trauma have been invisible and unsupported for far too long.

It is time, she says, to see, hear, and include these family members. To recognize their sacrifices and contributions, and empower them with research-based information, practical skills, and most of all hope in knowing they’re not alone.

After reading Michelle’s book, I’ll never think the same about Britney Spears—or her children—the same again.

I’d love to hear from any readers willing or able to share their thoughts or feelings about growing up with a parent who suffered from a MI.

Michelle D. Sherman has dedicated her career to supporting families dealing with a mental illness or trauma/PTSD and was named the American Psychological Family Psychologist of the Year in 2022. She served on the Board of Directors of NAMI-Oklahoma for fourteen years, and will join the Board of NAMI-MN-Ramsey County this summer. She also directed the Family Mental Health Program at the Oklahoma City V.A. for seventeen years where she developed education curricula/programs for families. One program, the Support and Family Education (SAFE) program was selected as a Best Practice nationally in the V.A. system.

I’m a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative with my “Minding the Gaps” column.

We’re a group of writers from all around the state and contribute commentary and feature stories of interest for those who care about Iowa and beyond.

We’re a group of writers from all around the state and contribute commentary and feature stories of interest for those who care about Iowa and beyond.

Click here to meet our writers and column topics.

Paid subscribers are also invited to the IWC “Office Lounge” held the last Friday of the month at noon. Here is the Zoom link for May 30!

In June 2020 I was attacked by 2 boxer dogs with 1 biting my thigh. The panic attacks I had after Grandpa Ralph (2006) and Mom (2011) died returned. Based on prior experiences I directly did some research and found a counselor. She said that a person doesn't have to go to war to have PTSD and that being attacked by dogs qualifies. I'm still scared of dogs which are loose or chained near sidewalks or leaning out car windows. Sometimes people say "oh my dog won't hurt you, it's just friendly!" Riiiiiight, I've got a bridge in Brooklyn I'm selling, dirt cheap, you want in on it?

It's an animal and something could set off any dog. I can't run very well or fast so I end up freezing until it's called off.

The podcast You’re Wrong About did a four part series about Britney Spears. It was very sympathetic to her and illuminating.